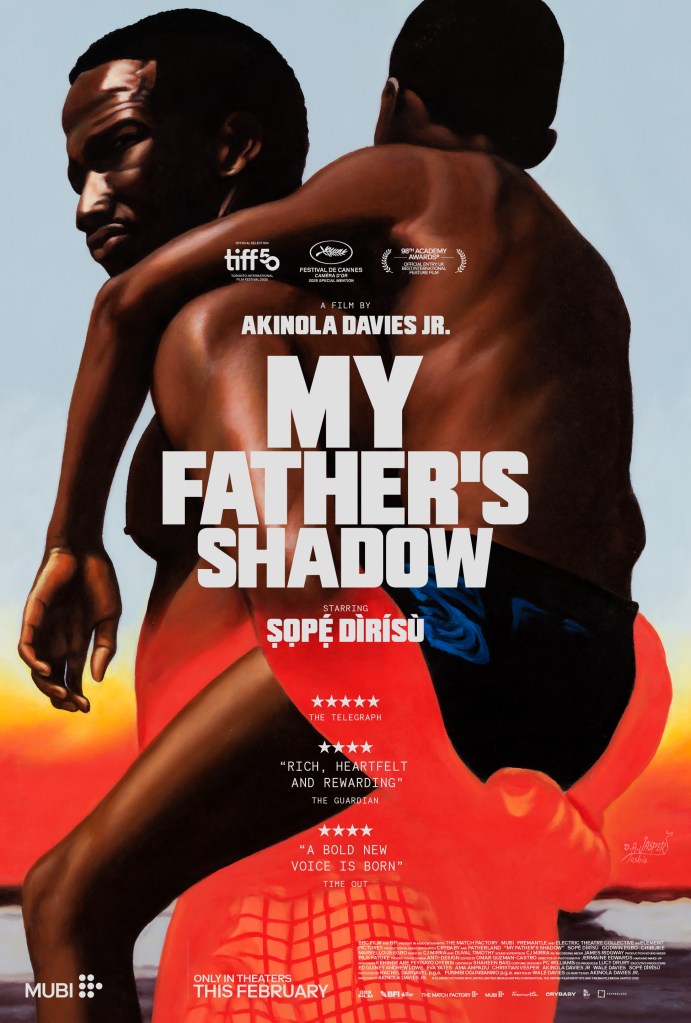

My Father’s Shadow (2025) – Review

Quick Thoughts:

- Between His House, Slow Horses, Gangs of London, Mr. Malcolm’s List and My Father’s Shadow, Ṣọpẹ Dìrísù has been on a great run.

- Director/co-writer Akinola Davies Jr. has crafted a confident film full of excellent performances and memorable visuals.

- The cinematography by Jermaine Canute Bradley Edwards is thoughtful and well-composed.

- It took 10 years for Akinola Davies Jr. and Wale Davis to get the film made, and I think it helped them because it gave them years to prepare, organize and plan.

- I love the WWE jokes (Kamala gets it bad).

Shot on location in Lagos, Nigeria, over eight weeks, My Father’s Shadow is loaded with intimate details that make its world feel alive and lived in. The cinematography, sound design, editing, and performances are top-notch, and I can’t wait to see what director Akinola Davis Jr. does next because he knocked his feature-length debut out of the park.

My Father’s Shadow revolves around a man named Folarin (Ṣọpẹ Dìrísù), and his two children, Akin (Godwin Egbo) and Remi (Chibuike Marvellous Egbo), having an eventful day in Lagos, Nigeria. Opening outside a beautifully detailed home in the Nigerian countryside, Akin and Remi pass their time alone (their mom is at work) playing with hand-drawn WWE wrestlers and bickering about food. Their father is rarely around as he works in Lagos (higher wages), and when the brothers talk about how they wish he was around more, he appears in the house, and agrees to take them to Lagos for a day trip so he can collect the six months of back pay owed to him from the shady supervisor at his factory job.

While in Lagos, the family visits the National Theater, stops by an empty amusement park, and swims in the Gulf of Guinea. They also talk about life/loss on a beach that’s home to a beached tanker boat (wonderful shot) and a dead whale that gets hacked to pieces by an opportunistic crowd. All the while, vultures circle above them, Folarin has constant nosebleeds, and the escalating political tensions surrounding a contentious presidential election threatens to cause chaos in Lagos.

In an interview with The Guardian, Dìrísù describes the film as being “a fantastical, pseudo-biographical piece of work about grief and loss and family, fatherhood, masculinity, connection and absence.” The explanation may sound like a lot, but it’s perfect in that it’s a film about a father reconnecting with his children during a politically turbulent day in 1993. The pseudo-biographical element comes from the fact that brothers Akinola Davies Jr. and Wale Davis made the film so they could explore their relationship with their father, who died when they were children. They grew up hearing stories about their “Larger-than-life” dad, and they eventually felt that they’d learned enough about him to create a three-dimensional character that would do him justice. The fantastical elements exist around the ever-present vultures who circle Folarin throughout the day, and their interactions with the Nigerian military, who have an ominous vibe punctuated by long stares and slow-motion. Also, in an interview, Davies Jr. talked about how dreams play an important part in Nigerian culture, so they made sure to bookend the movie with the idea with dream-like visuals. Perhaps the most powerful moment in the film is when Folarin talks about how he dreamt that his deceased brother’s spirit was worried about being forgotten, so he named one of his children after him to ensure his memory would survive. It’s an excellent monologue that’s shot confidently by Jermaine Canute Bradley Edwards.

The cinematography by Jermaine Canute Bradley Edwards is worth noting because the shot composition and framing are wonderful. Whether it’s rotting door frames, a colorful Ferris wheel, or a rusted tanker sitting on a Nigerian beach, Edwards found ways to find intimate visuals that made the world feel simultaneously real and mystical. Shot on KODAK 16mm (for cost reasons), the smaller infrastructure allowed the crew to move freely around their locations, which proved to be invaluable for the young cast members who were aided by the freedom the mobile camera allowed.

Final thoughts – Watch it. You will see it in your dreams.